Buses In Scotland - Why Are We In This Mess? 2000 - present

This is the sixth and final article in this series.

Access the last article in the series here: 1986 - 1999

2000 – present

The new problems that arose from the deregulation and privatisation of the bus industry in Scotland were predictable and the problems it was supposed to solve weren’t solved. It is obvious that the declining bus ridership throughout the 20th century is principally down to the decreasing overall cost of private cars and deregulation was never going to remedy that.

It was evident that deregulation would not address the entrenched problem of poor integration between the different operators. In fact, its design actively discouraged coordination between different modes, undermining any potential to challenge the convenience and coherence of the private car.

Yet still, we are toiling under the deregulated system.

At the opening of the new Scottish Parliament Liz Lochhead read a poem by Edwin Morgan (then-Makar) called “Open the Doors” containing the lines:

“What do the people want of the place? They want it to be filled with thinking persons as open and adventurous as its architecture. A nest of fearties is what they do not want. A symposium of procrastinators is what they do not want. A phalanx of forelock-tuggers is what they do not want. And perhaps above all the droopy mantra of ‘it wizny me’ is what they do not want.”

Full poem can be accessed here.

The new parliament passed its first Transport (Scotland) Act in 2001. Provisions were afforded in this Act for local transport authorities to enter into a Quality Contract Scheme (QCS) with private bus operators which were in effect a form of bus franchising.

Under a QCS, the local transport authority would set the routes and standards (but not fares) and tender these packages to private operators. There was also a section in this legislation which required them to make arrangements for integrated ticketing even between different operators. Local transport authority here means the local councils in Scotland except in Strathclyde where the local transport authority is SPT; this is a continuation of their role as the passenger transport executive which other areas of Scotland did not have.

In 2001, the McGill’s Buses name was revived by a new company which had bought over the Greenock bus depot previously owned by Arriva. This name had been used by a private bus company first incorporated in 1933 but hadn’t been used since 1998 after it was acquired by Arriva. The fact that the previous company operated out of Barrhead and not Greenock is neither here nor there.

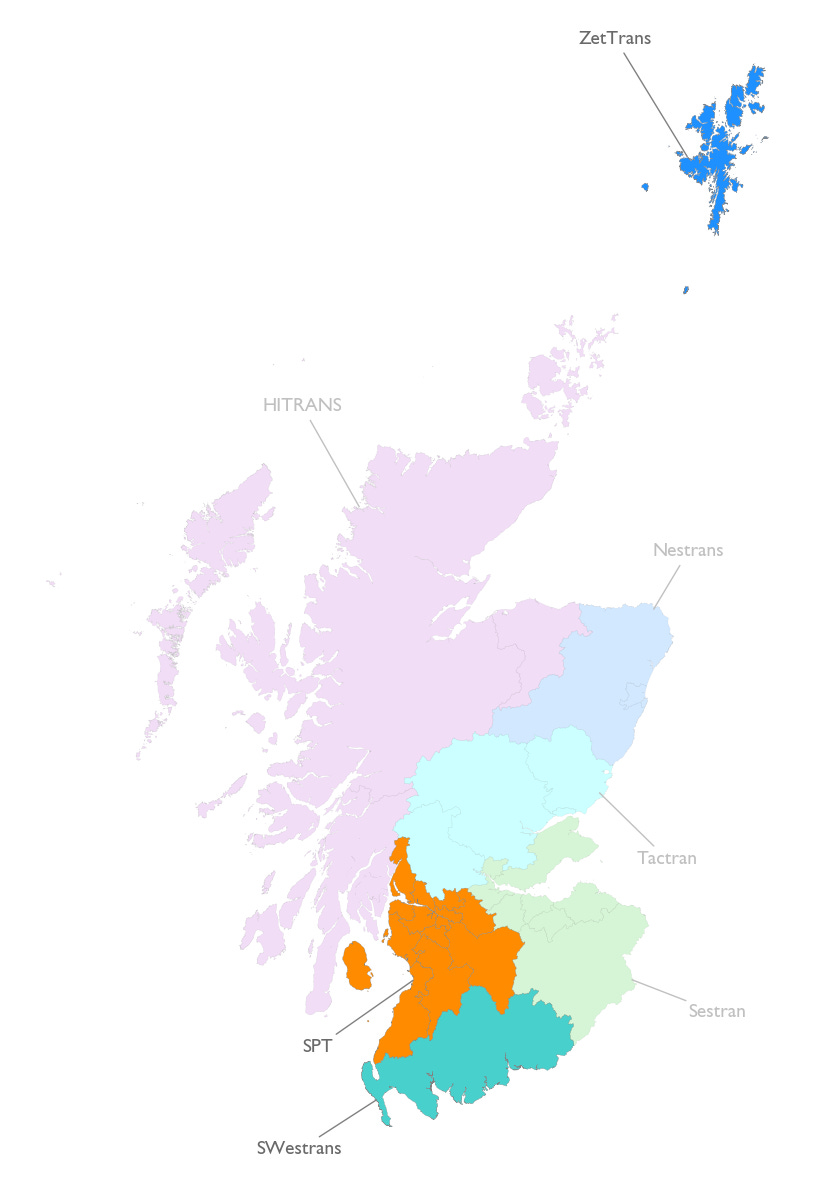

In 2005, there was another Transport (Scotland Act) passed. The Act created the seven Regional Transport Partnerships (RTPs), changing SPT’s name from Strathclyde Passenger Transport Authority to Strathclyde Partnership for Transport to maintain the acronym. The boards of these RTPs were made up by executive employees and councillors from the constituent councils.

The idea behind this restructuring was that transport policy should be developed regionally as common travel habits are not confined to council areas. They were tasked with developing regional transport strategies with awareness to meeting the needs of all inhabited places in those regions. These regional transport strategies are to be constantly under review.

There is a key distinction between regional transport partnership and local transport authority and although the 2005 Act established the RTPs, it did not confer upon them the status of local transport authorities. As a result, their roles have remained relatively constrained. SPT is the only Regional Transport Partnership that functions as a local transport authority across multiple council areas. SWestrans (Dumfries and Galloway) and ZetTrans (Shetland) are Regional Transport Partnerships whose area is contiguous with the local council.

In practice, this meant that only these three partnerships which are also local transport authorities (SPT, Swestrans and ZetTrans) could explore a QCS and in the rest of Scotland it would need to be the local council. This made it nearly impossible for many local transport authorities to meet the requirements for a QCS e.g. Clackmannanshire which has a total population of 52k and no profitable bus routes.

The Act moved the provision and regulation of local rail services from SPT to the Scottish Government, eventually phasing out the carmine and cream livery for the blue now used. This allowed the government to package up the whole of the rail network in Scotland into a single franchise which as of 2025 is operated by ScotRail on behalf of the Scottish Government.

In the mid-2010s, North East Combined Authority (NECA) attempted to implement a QCS scheme for Tyne and Wear using powers from the Local Transport Act 2008 which had similar provision to the 2001 Scottish Act except it added an independent panel as the final hurdle to implementing a QCS. This panel was to scrutinise the proposals and have ultimate decision-making power over whether the QCS could go ahead. The panel consisted of three people, one being the Traffic Commissioner, who were appointed by the UK Transport Minister.

In 2015, this panel rejected the NECA QCS proposal, claiming it would do disproportionate damage to operator profits. A consequence of this rejection was that no other English authority attempted to develop a QCS while this panel was in the legislation. This legislation was never workable. The panel was there to provide “checks and balances” but in playing that role it nullified the legislation as it made it too risky for other LTAs to create a QCS in case the same thing happened.

The Tyne and Wear QCS bid highlighted the self-immolative nature of the legislation and that it needed to be urgently replaced with something useable. In 2017, the Bus Services Act was passed in parliament which removed this panel and replaced it with an independent audit and a public consultation.

Now called franchising, this legislation was enacted successfully by Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham and Transport for Greater Manchester who now have an extensive publicly-controlled bus network which has flat fares, unified branding and integrated ticketing with trams, soon to have integrated ticketing with local train services.

By the end of the 2010s, no QCS had been pursued in Scotland due to the administrative burden placed on the LTAs in setting one up as well as the fear of being hung out to dry as the NECA were. It was also unclear, without full control of the fares, whether a QCS would have a big enough impact for passengers to justify the cost. There was also fear that given the timescale required to implement a QCS that private operators may improve services in the short term and thus undermine the potential benefits of the new scheme.

Following the Bus Services Act in 2017, the Scottish Government sought to follow suit and update the laws for bus regulation in Scotland by passing the Transport (Scotland) Act 2019. This Act ended up being an amalgamation of the 2008 and 2017 Acts in England, where it redesignated quality contract services as local services franchises, instituted an independent audit and public consultation in the process but also included the independent panel.

Seemingly learning nothing from the experiences of the NECA, the panel was added into Scottish legislation even though it hadn’t been in there before. The passing of the Bus Services Act 2017 was a tacit acknowledgement that this panel was unworkable and the prior legislation could never be enacted yet it was still added to the Transport (Scotland) Act 2019, two years later.

SPT are the only local transport authority currently testing this legislation through its Regional Transport Strategy and, within that, its Strathclyde Regional Bus Strategy which aims to return the control of the bus network to public hands through franchising and setting up a municipal bus operator once more.

A body created by the 1968 Transport Act, using powers from the 2019 Transport Act to return us to the control afforded by the 1930 Road Traffic Act.

It cannot be allowed to fail because of the opinion of three individuals; this would be catastrophic and set us back decades.

The SPT area features urban, rural and island communities and could provide the blueprint for the rest of Scotland to follow if they are ambitious in their plans.

Remember, the whole bus sector was deregulated, in part, to decrease the public subsidy to the bus companies? In 2023/24, £439 million of public money was paid out to bus companies in Scotland, accounting for well over half of their annual revenue, which adjusts to £143 million in 1985’s money. In 1985, total subsidy to bus companies in Scotland was £38 million.

It’s unequivocal that deregulation has failed to provide for passengers or workers, it has failed to improve services and, most importantly, it has failed to achieve its primary goal of reducing the cost to the public. We now pay twice for the privilege, once in government subsidy and again at the farebox. We have huge amount of public money propping up ailing private businesses yet we have no say in what they do with that money. This ludicrous system is why we are in this mess and it’s time we consign it to history.

A brilliant series of articles Paul 👏 Let's hope that all those at the "symposium of procrastinators" read them, and finally do something to sort out the mess!